Still’s disease

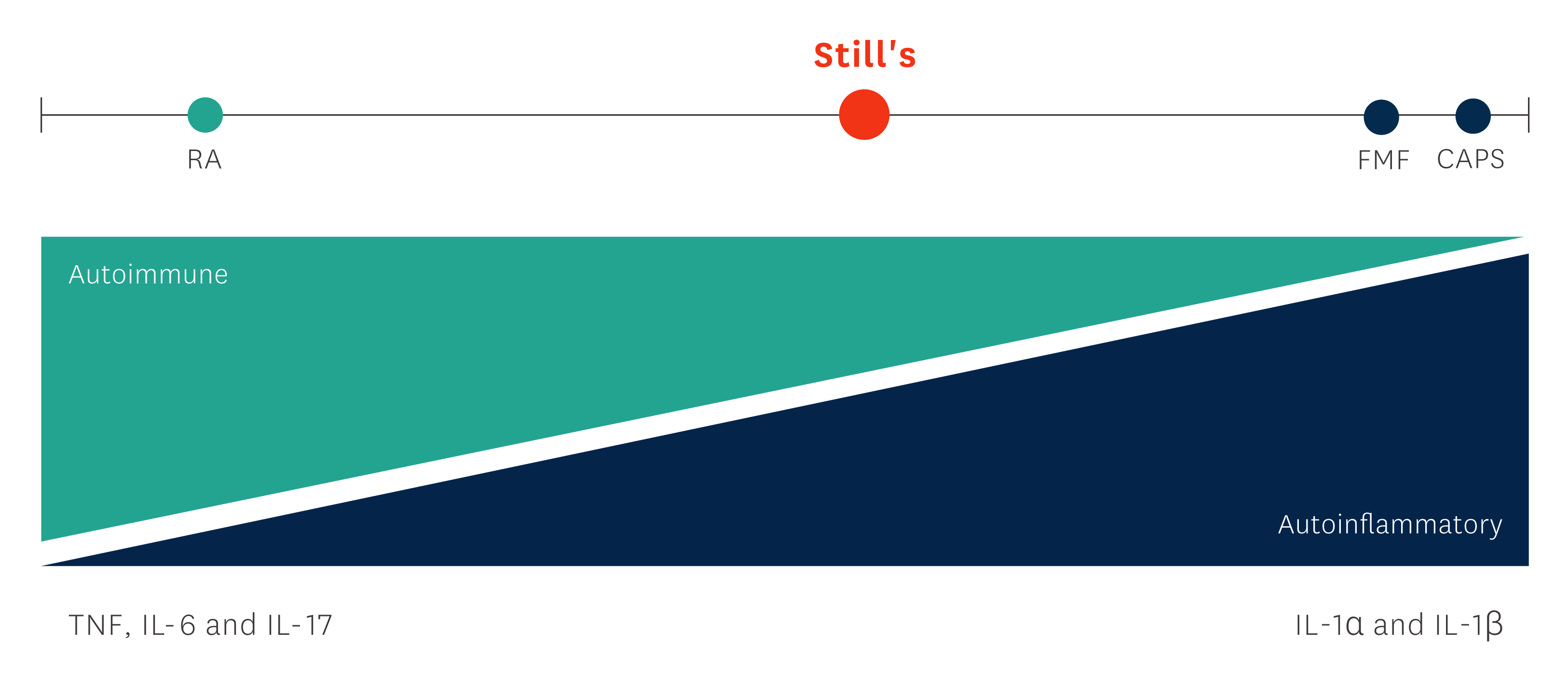

Still’s disease is a systemic inflammatory condition associated with activation of interleukin-1 (IL-1), a proinflammatory cytokine, with severely debilitating disease- and treatment-related morbidity that may significantly impair quality of life and lead to long-term disability, if not controlled.1-3

The following sections include further background information on this condition, introduce the proven efficacy and safety of Kineret in patients with Still’s disease, and provide appropriate guidance on dosing and administration of Kineret.

Disease background

Still's disease is a systemic inflammatory condition associated with activation of the proinflammatory cytokine interleukin-1 (IL-1), and characterised by severely debilitating disease- and treatment-related morbidity.1, 4, 5

In children, Still's disease is also often referred to as Systemic-onset Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis (SJIA). Both SJIA and Adult-Onset Still's disease (AOSD) belong to the autoinflammatory Still's disease continuum and share a similar genetic aetiology, clinical presentation, and disease course.5, 6

Common symptoms4,8,10

- Spiking fever, often on a daily basis

- Arthralgia or arthritis

- Salmon-coloured, evanescent skin rash

- Enlarged liver and/or spleen

- Serositis (organ-lining inflammation)

- Lymphadenopathy

- Sore throat (increased frequency in patients with AOSD)

- Laboratory abnormalities, e.g. an increase in acute phase reactants (ESR, CRP, serum ferritin)

Efficacy

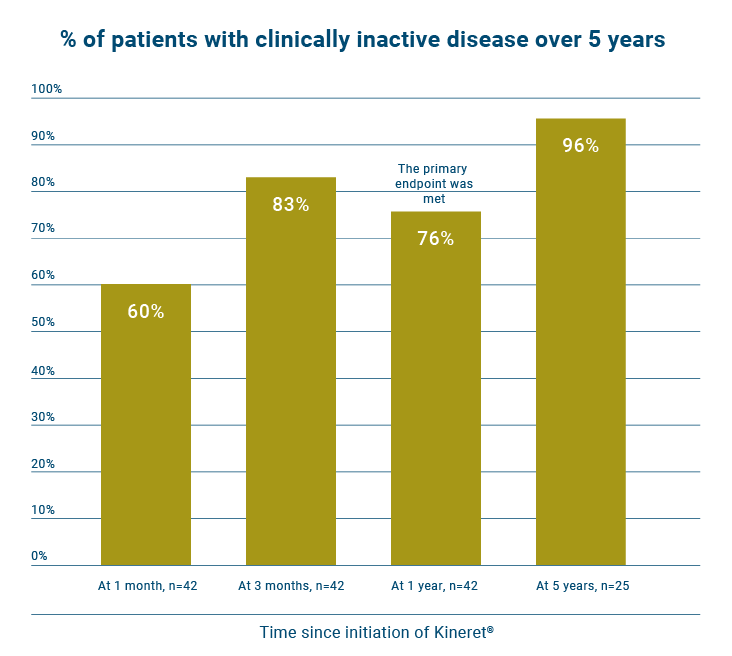

Early treatment with Kineret can provide long-term remission in patients with sJIA.13

A single-centre prospective study evaluated a treat-to-target approach in new onset sJIA patients using Kineret as first-line monotherapy to achieve early inactive disease and prevent damage. Patients were also monitored for adverse events.13

Patients

42 patients with new-onset sJIA with an unsatisfactory response to NSAIDs received Kineret monotherapy according to a treat-to-target strategy. Of these, 12 had no arthritis at disease onset. Patients with an incomplete response to 2 mg/kg Kineret (with a maximum of 100 mg/day for patients weighing >50 kg) subsequently received 4 mg/kg Kineret or additional prednisolone or switched to alternative therapy. For patients in whom inactive disease was achieved, Kineret was tapered after 3 months and subsequently stopped.

Study endpoints

Primary endpoint was clinically inactive disease 1 year after initiation of Kineret. Secondary measure was the percentage of patients in whom inactive disease was achieved with Kineret monotherapy, as well as the percentage of patients with inactive disease while not receiving medication.

Key definitions of response

Clinically inactive disease was defined according to the modified Wallace criteria as the absence of arthritis, morning stiffness, and systemic features; a physician’s global assessment indicating no disease activity (<10 on a scale of 0-100); and normalisation of ESR (<20 mm/hour) and CRP level (<10 mg/L).

Patient baseline characteristics

Patient groups were comparable at baseline except for the number of joints with active disease.13

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

*Except where indicated otherwise, values are the median (interquartile range). Ordinal variables were compared using Fisher's exact test and continuous variables were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test. †P < 0.001 versus patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) with arthritis. All other comparisons were nonsignificant.

Kineret provided a quick and sustained response in a substantial proportion of the new onset sJIA patients.13

- At 1 month, 60% (n=25/42) of patients had inactive disease.

- At 1 year, 76 % (n=32/42) of patients had inactive disease.

- At 5 years, 96% (n=24/25) of patients had inactive disease.

In the study, patients were also monitored for adverse events. No patient stopped Kineret due to infections or other serious adverse events. In total, four patients developed MAS during their disease course. One of these, with severe disease refractory to Kineret, MTX, tocilizumab, canakinumab, and glucocorticoids, died due to macrophage activation syndrome 2 years after the start of therapy.13

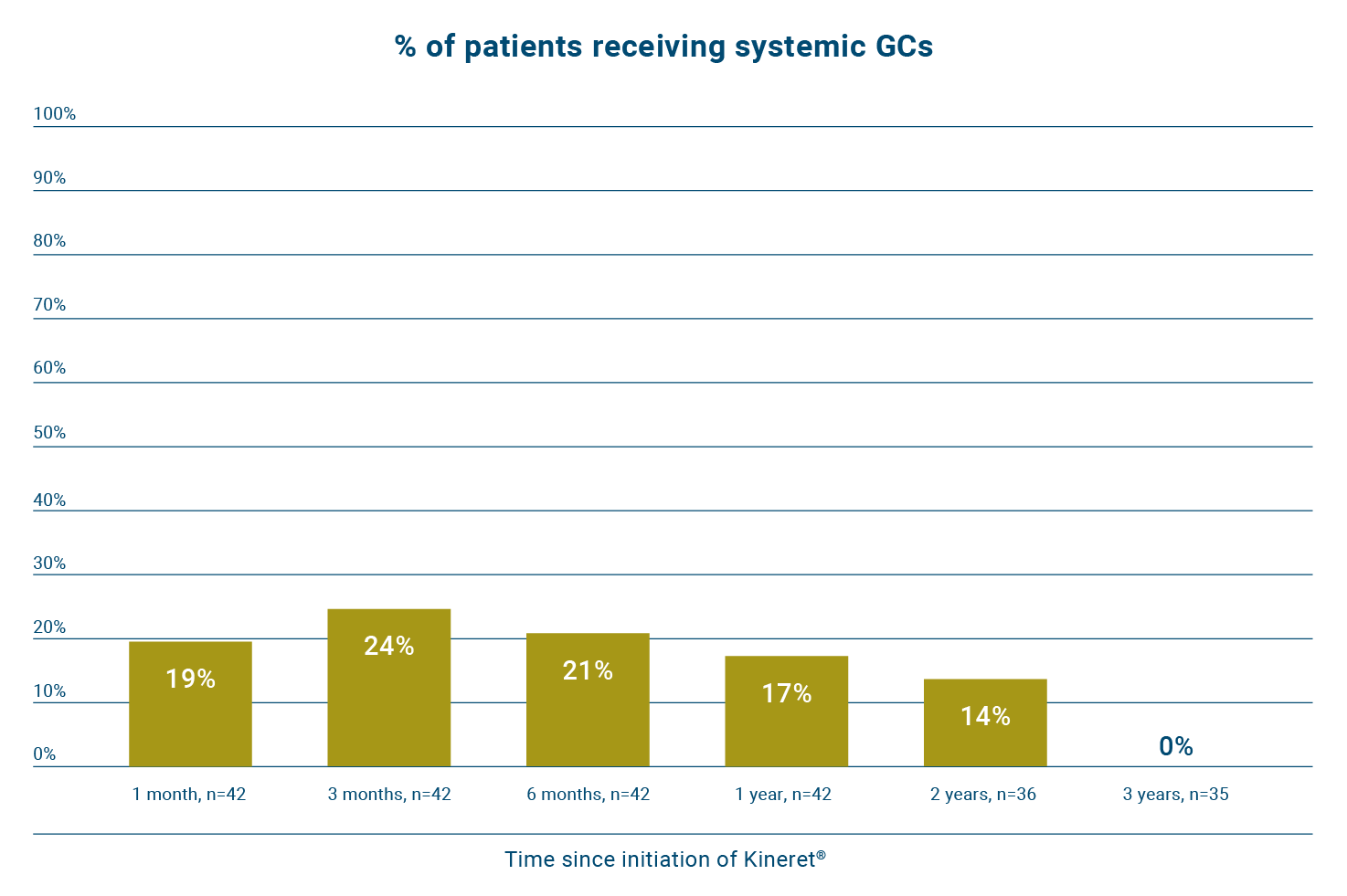

Early treatment of sJIA with Kineret can help reduce patients’ long-term exposure to glucocorticoids.13

In the same study, 57% of patients (n=24/42) did not require glucocorticoids to sustain inactive disease during follow-up.13

Early treatment with Kineret shows numeric differences in efficacy vs DMARDs in AOSD symptoms.14

An open-label, randomised, multicentre study investigated the efficacy of Kineret versus DMARDs in AOSD patients that were refractory to corticosteroid treatment.14

Patients

22 AOSD patients from 10 centres in Finland, Norway and Sweden (12 on Kineret and 10 on DMARD). The trial was originally powered to recruit 30 patients in each group.

Key inclusion criteria

AOSD diagnosed according to Yamaguchi et al. classification; treatment with corticosteroid and possible DMARD for ≥2 months before randomisation; refractory to corticosteroids and DMARD, defined as active disease despite prednisolone treatment (≥20 mg/day) with or without concomitant DMARD.

Primary endpoint

Remission according to specific criteria at 8 weeks: afebrile (≤37°C body temperature, measured twice from the armpit) in absence of NSAID 24 hours prior to measurement; decrease of CRP to 10 mg/L and ferritin to 200 μg/L in females and 275 μg/L in males; normal swollen joint count to tender joint count ratio. Please note, the primary endpoint in this study was not met.

There was a numerical difference at all times; however, these differences did not reach statistical significance.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure adapted from Nordström D et al, 2012.14

Patient baseline characteristics

Patient groups were comparable except for baseline ferritin and prednisolone dose.14

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

*Significant difference (p < 0.001).

In the study, three patients experienced serious adverse events, defined as worsening of AOSD (lack of efficacy) in one on Kineret and two on DMARDs. Seven patients receiving Kineret reported grade 1 ISRs and one patient reported a grade 2 ISR. During an open-label extension, four additional patients reported a grade 1 ISR. No subject withdrew from the study due to ISRs.14

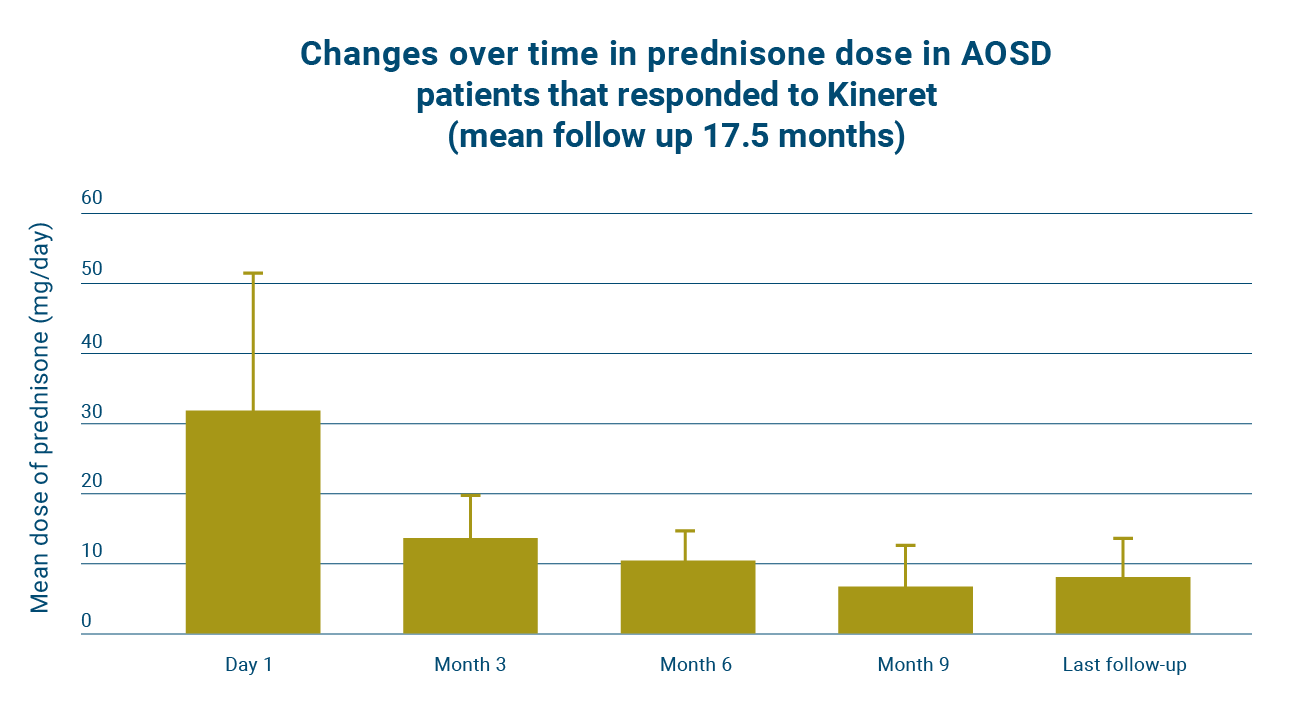

Early treatment of AOSD with Kineret can help reduce patients’ long-term exposure to glucocorticoids.15

One study assessed the efficacy and safety of Kineret treatment in sJIA and AOSD patients. Please note that this study was not randomised or controlled.15

Patients

A total of 35 patients were included in the study, 20 with sJIA and 15 with AOSD.

Key inclusion criteria

AOSD patients had to fulfil the Yamaguchi criteria for AOSD. sJIA patients had to fulfil the International League Against Rheumatism criteria for sJIA.

Key measure

Effect of Kineret treatment on systemic features including fever, skin rash, ESR or CRP levels, and on other disease markers before starting treatment (tender joint, swollen joint count, physician’s and patient’s or parent’s assessment of disease activity or pain on a visual analogue scale) at 3 months, 6 months and the latest follow-up. 11 patients with AOSD achieved at least a 50% improvement for all disease markers.

Key definition of response

In AOSD patients, response was defined as resolution of systemic symptoms and an improvement of the ACR score by at least 20%. In sJIA patients, response was defined as resolution of systemic symptoms and the improvement of Giannini’s ACR Paediatric core set criteria by at least 30% for polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis activity assessment.

Patient baseline characteristics

Patient groups were comparable at baseline except for in age and daily prednisone dosage.15

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

*In three patients with sJIA, evanescent rash was present in the absence of fever. †The average and maximum doses of MTX received prior to anakinra treatment were 0.6 mg/kg/week and 1 mg/kg/week, respectively. The average and maximum doses of MTX received prior to anakinra treatment were 20 mg/week and 30 mg/week respectively. ‡Rituximab (n = 1) and cyclophosphamide (n = 1) for sJIA patients; rituximab (n = 2), cyclophosphamide (n = 1), mycophenolate mofetil (n = 1), azathioprin (n = 1) and sulphasalazin (n = 1) for AOSD patients.

Two patients with AOSD stopped taking glucocorticoids and 8 patients reduced their glucocorticoids intake by 45–95% with Kineret.15

Two sJIA patients stopped anakinra treatment during the first 3 months, and three patients stopped treatment between the months 3 and 6. Treatment withdrawal, in these five patients, was either due to intolerance (one case) or a lack of efficacy (four cases).

ACR, American College of Rheumatology; AOSD, Adult-Onset Still's disease; AZA, azathioprine; CAPS, Cryopyrin-Associated Periodic Syndromes; CRP, C-reactive protein; DMARD, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; FMF, Familial Mediterranean fever; GC, glucocorticoid; IL, interleukin; ISR, injection site reaction; IVIG, intravenous immunoglobulins; LEF, leflunomide; MAS, macrophage activation syndrome; MTX, methotrexate; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug; RA, Rheumatoid Arthritis; sJIA, Systemic-onset Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis; TNF, tumour necrosis factor.

References:

- Kineret Summary of Product Characteristics. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/559/smpc (Accessed May 2025).

- Consolaro A, et al. Pediatric Rheumatol . 2016;14:23.

- Pascual V, et al. J Exp Med. 2005;201(9):1479–86.

- Giacomelli R, et al. J Autoimmun. 2018;93:24–36.

- Vastert SJ, et al.Rheumatology. 2019;58(Suppl 6):vi9–vi22.

- Nigrovic PA, et al. R Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70:7–17.

- McGonagle D, McDermott MF. PLos Med . 2006;3(8):e297.

- Woo, P. Nat Clin Pract. 2006;2:28–34.

- Efthimiou P,et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65(5):564–72.

- Jamilloux Y, et al. Immunol Res. 2015;61(1–2):53–62.

- Spiegel LR, et al. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43(11):2402–9.

- Vastert SJ, et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(4):1034–43.

- ter Haar NM, et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(7):1163–1173.

- Nordström D, et al. J Rheumatol. 2012;39(10):2008–2011.

- Lequerré T, et al. Ann Rheum Dise. 2008;67(3):302–318.

Adverse events should be reported. Reporting forms and information can be found at www.mhra.gov.uk/yellowcard or search MHRA Yellow Card in the Google Play or Apple App Store (for United Kingdom) and www.hpra.ie (for Republic of Ireland). Adverse events should also be reported to Swedish Orphan Biovitrum Ltd at [email protected] or Telephone +44 (0) 800 111 4754